What is Aesthetics?

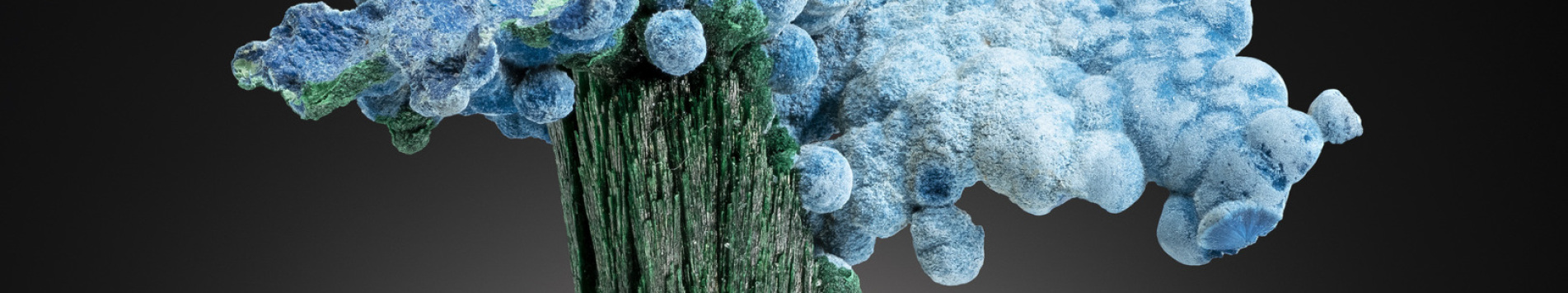

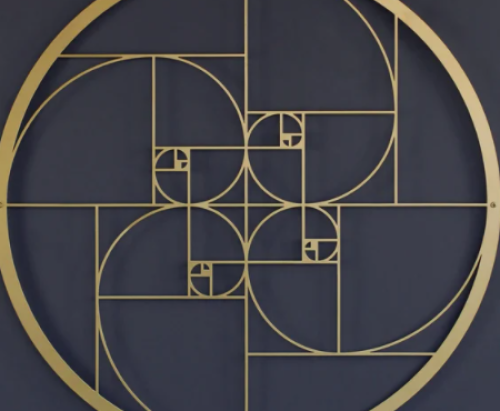

Aesthetics (from the ancient Greek αἴσθησις aísthēsis, meaning “perception” or “sensation”) was, up until the 19th century, primarily concerned with the study of

beauty, regularity, and harmony in nature and art.

Literally, aesthetics means the study of perception—particularly sensory perception. Accordingly, anything that moves or stimulates our senses when we observe it is

considered aesthetic: not only the beautiful or pleasant, but also the ugly or unpleasant. A philosophical approach focused exclusively on beauty is referred to as callistics.

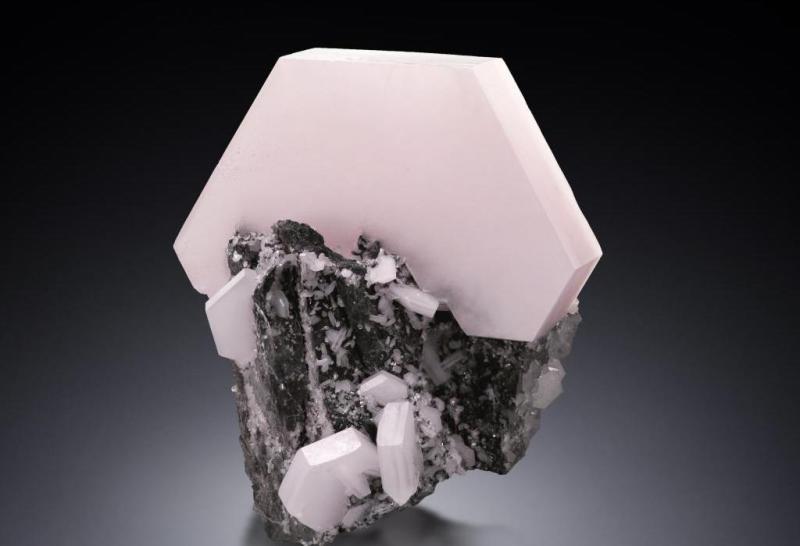

In everyday language today, the term aesthetic is often used synonymously with “beautiful,” “tasteful,” or “appealing.” In a scientific or philosophical context,

however, the term is more nuanced. In a narrower sense, it refers to the qualities that influence how people judge something from the perspective of beauty. In a broader sense, it encompasses all

attributes that affect how an object is perceived and experienced.

(Source: Wikipedia)